Epistemic risks under Knightian uncertainty

Engaging with Lara Buchak’s wonderful review of my 2021 book, Epistemic Risk and the Demands of Rationality, has made me think again of William James and his two maxims—Believe truth! Shun error! James’ central insight was that they pull in opposite directions, the first pushing us to believe more, in the hope that we hit upon some truths among those beliefs, the second pushing us to believe less in the fear that we hit upon some falsehoods by doing otherwise. As a result, if we are to act in accordance with them, we must specify the weight we give to each.

In the book, as well as in this earlier paper, I noted that there are at least two ways we might try to make James’ idea precise—indeed, the earlier paper was called ‘Jamesian Epistemology Formalized’. On the first, the weights we give to the two maxims are reflected in the way we value beliefs. For instance, if I give greater weight to Shun error! and less to Believe truth!, that might be reflected in the fact that I give moderate positive epistemic utility to believing a truth, but very substantial negative epistemic utility to believing a falsehood. On the second way of making James precise, the weights are reflected not in our values, but in the decision rule into which we feed our values in order to make our epistemic decisions, such as what to believe and what credences to assign. In this post, I’ll be particular interested in our choice of prior credences, and so I’m interested in how we pick these—though I’ll talk of posteriors at the end. When we are picking posteriors, we have some probabilities that we might think should guide us—namely, our priors—and so it might be natural to use a decision rule that takes as input credences as well as utilities (and possibly some other attitudes too); for instance, we might use expected utility theory. But when we are picking our priors, there are no probabilities around that should guide us—as I noted in this previous post, I don’t think there are evidential probabilities, which some take to govern our decision in this case. So, we need a decision rule that does not take probabilities as an input—it takes values, represented as utilities (and possibly other sorts of attitudes).

In my earlier paper, I suggested the natural rule to use to formalise James’ thesis is the Hurwicz Criterion: this assigns a score to each available option by taking a weighted sum of its maximum utility—the highest utility it could obtain for us—and its minimum utility—the lowest utility it could possibly obtain for us; and then it exhorts us to pick one with maximal score. The weights, Hurwicz proposed, reflect the decision-maker’s optimism or pessimism. The more weight given to the maximum, the more optimistic; the more given to the minimum, the more pessimistic. But our ordinary notions of optimism and pessimism are epistemic ones: the optimist believes more strongly that the best outcome will come about; and the pessimist believes more strongly the worst happen. And we don’t want something epistemic, because we’re using this rule precisely to set our initial epistemic state. Instead, then, we might say that the weights reflect our attitudes to epistemic risk: the greater the weight we give to the maximum, the more risk-seeking we are; the greater the weight we give to the minimum, the more risk-averse. And, we might naturally take these to be the weights we give to James’ two maxims as well. Those who give greater weight to Believe truth! are those who give greater weight to the best-case outcome, and when you have a belief, that’s the outcome at any state at which it’s true, and when you assign credences, it’s the outcome at any state at which the credence is highest—they are the epistemic risk-seekers. On the other hand, those who give greater weight to Shun error! are those who give greater weight to the worst-case outcome, and when you have a belief, that’s the outcome at any state at which it’s false, and when you assign credences, it’s the outcome at any state at which the credence is lowest—they are the epistemic risk-avoiders.

So the Hurwicz Criterion seems a reasonable way to formalise James’ central idea—and I generalized it in Epistemic Risk and the Demands of Rationality so that you give weights not just to the best- and worst-case outcomes, but to each of the positions from best-, second-best-, third-best-, and so on down to second-worst, and worst. But both the original version and my generalization are what we might think of as maximising decision rules. That is, they proceed by defining a score for options, and then saying we should pick an option that maximises that score. In this post, I’d like to propose what we might think of as a sufficientarian decision rule. I think it might better capture how we think of risky decisions in the absence of probabilities to guide them. It is inspired by a suggestion that Sophie Horowitz makes, almost in passing, in her ‘Immoderately Rational’.

The idea is very roughly this—we’ll have to amend this initial formulation significantly, but it sets the stage. In the absence of probabilities, we set a threshold above which must lie the minimum possible utility an option can give us and we set a threshold above which must lie the maximum possible utility it can give us. Given a decision problem, the permissible options are then those among the available options whose minimum utility is greater than the first threshold, whose maximum utility is greater than the second threshold, and which are not dominated by any available option.

Of course, this can’t be all there is to the decision rule, because we might face a decision in which no option clears both thresholds, and in that case the account I’ve just given would render all options impermissible. So what it seems we need is a fallback pair of thresholds to use if nothing clears the first pair; and then of course we need a further fallback pair to use if nothing clears the second pair; and so on. In fact, I think we need something a little more technically involved to give the most plausible version of this theory. I’ll sketch it here, but it’s really just a slightly more elaborate version of what I’ve just described.

For the purpose of spelling out the theory, let’s suppose there is some greatest utility that we might ever obtain from any possible options—for convenience, let’s say it’s 10—and also some least utility—for convenience, let’s say it’s 0. Then what we need is a pair of continuous functions, l and h, each taking as its argument numbers between 0 and 1 inclusive and returning numbers between 0 and 10 inclusive, and such that l(0) = h(0) = 10 and l(1) = h(1) = 0. Given these, and given a particular decision problem, we define the set of numbers t between 0 and 1 inclusive such that there is an available option in that decision problem that has minimum utility at least l(t) and maximum utility at least h(t). Then we take the infimum t* of that set. And finally we say that an option available in this decision problem is permissible if, and only if, (i) its minimum utility is at least l(t*), (ii) its maximum is at least h(t*), and (iii) it is not dominated by any other option in that decision problem. And we can show that this is not an empty set.

Here’s an example of a pair of functions, h (orange) and l (blue):

Now, suppose we face a decision between two options defined over two states of the world: the first gives 4 units of utility at the first world and 3 at the second; the second gives 1 unit at the first and 5 units at the second. Then the green dashed lines correspond to the maximum and minimum utilities of the first option, and the pink dashed lines do the same for the second option. An option becomes permissible when both of its lines have crossed the l and h functions. This occurs first for the second option (around t = 0.7) and later for the first option (around t = 0.95). And so t* is around 0.7, and the only permissible option is the second one.

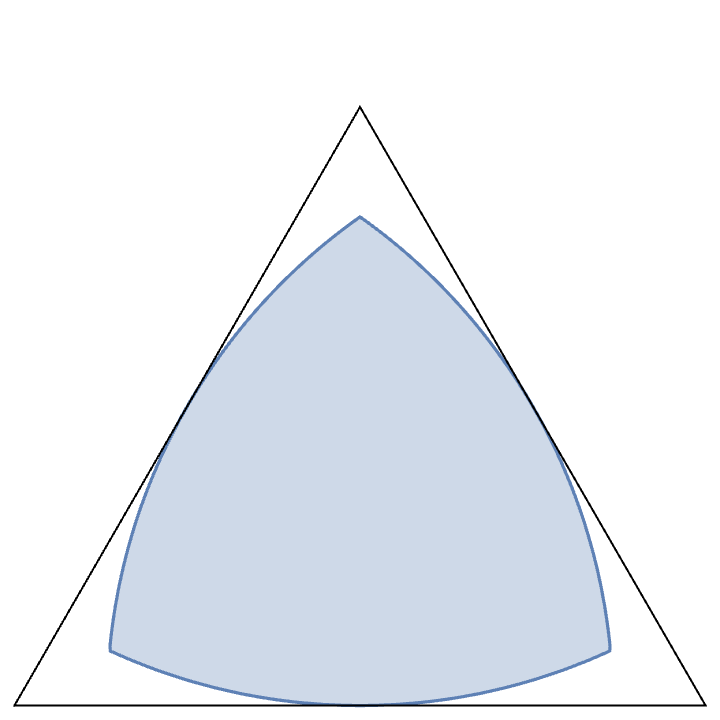

Now let’s see how this plays out in the epistemic case. For the purposes of illustration, we’ll consider the case in which you are assigning credences to just three states of the world. We can then represent your credences in a barycentric plot as follows: we plot our credences in a triangle; each corner of the triangle corresponds to one of the three states of the world; it represents the credence function that give all of its credence to that world; each probability function over the three worlds is then a weighted average of these three credence functions at the points; the weights are the probabilities it assigns to the states of the world; so the centre of the triangle, which gives equal weight to each, represents the credence function that gives 1/3 to each state.

I’ll use two different ways of measuring the epistemic value of an assignment of credences. The first is the Brier score;1 the second is the log score.2 Let’s see what our decision rule says when it’s fed epistemic utilities from the Brier score and different thresholds for minimum (l) and maximum (h) utilities.

And now let’s see what our decision rule says when it’s fed with the log score and different thresholds.

As we can see, the greater the threshold is on the minimum utility—that is, l—the less extreme the most extreme credences it permits. This makes sense, since a greater threshold reflects greater aversion to risk. The greater h is, the less equivocating are the most equivocating credences it permits. Again, this makes sense, since the greater threshold here reflects greater inclination towards risk.

So this decision rule tells us how to pick priors. But what to do about posteriors? In Epistemic Risk and the Demands of Rationality, I argued that, at that point, when we have our prior credences set and presumably take them to have some normative authority over what we do, we should use expected utility theory, fed with those priors and our epistemic utilities, to pick our posteriors—and I appealed to a suggestion by Dmitri Gallow to argue this approach tells us to update our priors by conditioning on our evidence to give our posteriors in exactly the way the standard Bayesian requires.

But there is an alternative. Let’s suppose you know the first evidence you’ll obtain after you set your prior will come from a particular partition: you’ll look out the window and learn it’s raining or it’s not raining, for instance. Now, before you receive the evidence, you can plan how you’ll update: if I learn it’s raining, I’ll do this; if I learn it’s not, I’ll do that. And of course we can score these plans for their epistemic utility: the epistemic utility of an updating plan at a state of the world is the epistemic utility of the posterior obtained by updating on whatever evidence you obtain at that state—the evidence that it’s raining at states in which it is, and the evidence it’s not raining at states in which it isn’t. There are a few arguments that, if we think of things in this way, considerations of epistemic utility tell in favour of Bayesian conditioning.3 So let’s assume you’ll do that. Then this suggests that, when picking your prior, you should take into account not only the minimum and maximum epistemic utilities of that prior, but also the minimum and maximum epistemic utilities of the posterior it will lead you to have.

Now, whether that has an effect on the choice of priors, and if it does what effect, depends on how you are measuring epistemic value. If you are using the log score, it has no effect, since learning a true proposition always increases your credence in the true state of the world and so increases your log score. If, on the other hand, you are using the Brier score, a prior might be permissible when considered on its own, but, if we apply our decision rule also to the updating plan it requires, it is no longer permissible because the minimum epistemic utility it will achieve has now fallen below the threshold.4

We can see this happening in an example. Let’s suppose there are three states of the world: It’s raining and it’s windy; It’s raining and it’s not windy; It’s not raining. And let’s suppose you assign credences 10%, 70%, 30%, respectively. And suppose by looking out the window you’ll learn whether it’s raining or it’s not, but you’ll learn nothing about whether it’s windy. That is, either you’ll learn that the world is the first or the second, or you’ll learn it’s the third. And you’ll update by conditioning on this evidence. Then, if you use the Brier score and your threshold for minimum utility is 0.5 and so is your threshold for maximum utility, then the prior on its own is permissible, since its minimum possible utility occurs at the first world, and it is 0.55333; but it is not permissible as a starting point on which to condition when you receive evidence, because the minimum possible utility of a possible posterior to which it will give rise is 0.489583, which obtains at the first world, where you learn it’s raining and update your credences on that.

The Brier score of an assignment (p1, p2, p3) at world wi is

The log score is (p1, p2, p3) at world wi is

This is a little like Jason Konek’s proposal in his ‘Probabilistic Knowledge and Cognitive Ability’, which also looks at the epistemic utility of your posteriors to judge your priors.